Despite unprecedented protectionism, the sector is in a state of “free fall.” Official producer data show that in January more than 3.5–5 thousand hectares of the 2025 crop remain under snow; with an average yield of 50 tons per hectare, this amounts to roughly 200–250 thousand tons of sugar beet. This means that dozens of farmers and two sugar-producing companies will not avoid multi-million losses.

“Rain, fog, and low temperatures in autumn didn’t allow us to harvest on time, and winter arrived unexpectedly, with frosts down to -10 to -15 degrees Celsius. Harvesting stopped, and no one can predict what will happen next. In my 55 years of work, I have never seen a sugar plant stop twice during a season because it ran out of beet. These are losses for the plant and losses for us, the agricultural producers,” laments Vasile Grădinaru, a farmer from the village of Șuri, Drochia district.

In a certain sense, the farmer’s view is shared by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (MAIA).

“Harvesting sugar beet with a combine became extremely difficult. For example, in November there were only three or four ‘windows’ when farmers could take machinery into the fields. Now they are waiting for temperatures to rise slightly so that it becomes possible to dig beets out of frozen soil. However, it should be understood that harvesting during such periods is a rather complicated process. Machinery breaks down and fails,” emphasized Grigori Baltag, head of the Crop Policy Directorate at MAIA.

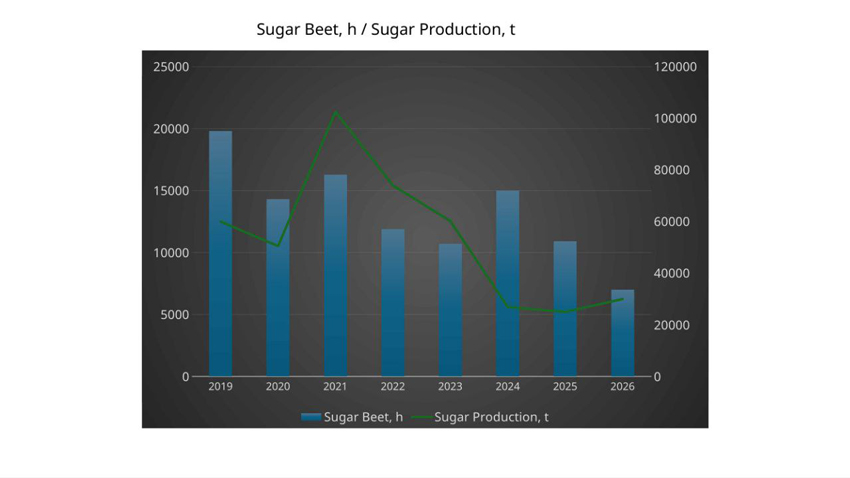

Hypothetically, the problems faced by Moldova’s beet growers and sugar producers in the 2025 agricultural season could be attributed solely to the “whims of nature.” However, the sector’s involution over the past five years suggests the main cause lies elsewhere. Statistical data show that over this period, sugar-beet planted area in the country fell from 24 thousand hectares to 11 thousand hectares, while beet processing volumes dropped from 1 million tons to 300 thousand tons in 2024; accordingly, 2025 should have been a normal year without excessive risks. But the harvest campaign was not properly organized.

Apparently, this is not the bottom of the decline. Considering global market conditions, decisions by major EU sugar-market players, and the production and financial situation of Moldova’s sugar producers, one may assume that in spring the contracted areas for the 2026 crop will shrink substantially; in a pessimistic scenario—by 1.5 to 2 times, down to 5–6 thousand hectares.

A situation where, under a 75% duty, the sector cannot supply even 50% of domestic demand indicates a profound management crisis.

Moldova’s sugar producers have built a business model in which all operational risks and the costs of inefficient management are shifted onto other links in the chain. Farmers complain not only about the weather but also about logistical disruptions and unjustified technical stoppages at factories even during favorable periods. In the 2025 season, dozens of farmers were left with crops under snow (around 200–250 thousand tons of beet) while not receiving payment for the previous year. At the same time, industrial consumers complain that Moldova’s wholesale sugar price (15–16 lei/kg) is 1.5–2 times higher than in neighboring countries and the EU. For the food industry—where sugar accounts for 25–40% of product cost (jams, sweets, beverages)—this means a loss of competitiveness and a threat to 30 thousand jobs in related sectors. Yet the sector continually demands subsidies, emergency financial support for re-sowing, and trade-protection measures, effectively turning into a “black hole” for the budget.

|

Sugar in Foods |

|

|

Product |

Average Share |

| Ice cream |

20-25% |

| Jams/marmalade |

40-60% |

| Chocolate |

50-60% |

| Cocoa-based creams |

50% |

| Cookies and confectionery |

15-20% |

| Carbonated drinks and juice drinks |

10-20% |

| Dairy products containing sugar |

7-18% |

The minimum “survival norm” for each plant is not a slogan but mathematics: roughly 10–12 thousand hectares of sugar beet per plant at yields around 50 t/ha. Only such a raw-material base allows costs to approach a competitive level. However, practice shows that after the last two failed agricultural seasons, farmers’ trust in processing-sector counterparties inevitably “breaks.” In 2025, we observed not only disruptions in beet harvesting due to bad weather, but also logistical delays in September and November, as well as unjustified technical stoppages when weather conditions were good. In the current season—when farmers have not been paid for the previous year’s crop and sugar companies face enormous financial difficulties—an even tougher scenario is emerging: in total, only 5–7 thousand hectares may be planted for two plants. In that case, it is far from certain that both sugar factories will continue operating. The outcome is that Moldova’s beet-and-sugar sector will not be able to reliably cover 50% of domestic sugar demand from its own production,” said Yuri Rija, an agriculture expert.

Moreover, Mr. Octavian Calmîc, chairman of the “LEX-ECON Consulting” Association and former Minister of Economy, clarifies that “international market prices have fallen sharply, making this sector unattractive and higher-risk, especially for farmers. Compensating inefficiency in this sector through trade-protection measures or state subsidies will lead to financial problems and to the non-competitiveness of related processing industries, particularly in the European market.”

It should be borne in mind that even in conditions of several years without exports and tightly limited sugar imports (by the size of preferential quotas), Moldova is not isolated from the influence of the global—and especially the European—sugar market. And that market is experiencing a deep downturn. In the previous season, five major EU sugar plants suspended operations; at least three more Eastern European sugar plants are considering preparations for closure/suspension amid unfavorable climatic dynamics in recent seasons, a shrinking raw-material base, and a global sugar surplus that pressures prices and margins. This reinforces the broader trend: European producers are shifting from “growth” to “contraction”—reducing plantings, optimizing capacity, and shutting down unprofitable sites.

By early 2026, wholesale sugar prices in Germany, Poland, and France fell by about 20% compared to a year earlier, down to around 400 euros/ton (producer level). European market operators are skeptical about any near-term strengthening of sugar prices due to the global surplus. In this reality, for example, Südzucker AG (Germany) has already announced a significant 35% reduction in contracted sugar-beet area for the new crop.

On Moldova’s wholesale market, the current sugar price remains at 15–16 lei/kg; in retail—no less than 18 lei/kg. That is, Moldovan household and, more importantly, industrial sugar consumers pay 1.5–2 times more for this product (and for a key input into food production) than consumers in neighboring countries and in the European Union overall. For Moldova’s food industry, this implies a critical loss of competitiveness—both domestically (a market not protected from imports of sugar-containing products) and on all external markets. According to expert estimates, this is a sector employing at least 30 thousand people.

Another curious fact. As Mr. Calmîc claims, “the duty-free EU quota (9 thousand tons) was used by 88%, and the preferential WTO quota (10% duty, 1 thousand tons) for importing sugar into Moldova was fully used on the very first working day of 2026. About 90% of these quotas combined were taken up by Moldovan sugar-producing companies (Südzucker Moldova and Moldova Zahăr). In other words, sugar producers intend to maintain their status as monopolists and price-setters on Moldova’s sugar market and prevent price decreases for domestic consumers. Under such a setup, the likelihood that sugar prices in Moldova will remain high increases.”

Even in official government documents, Moldova’s beet-and-sugar sector is listed as one of the most protected in the real economy. Its “assets” include:

- initially, extended special tariff safeguard measures (cumulatively, for more than a decade);

- the highest customs duties on imports into Moldova (around 75% since 2021);

- sugar excluded from most free-trade agreements signed by Moldova; at the end of 2025, temporary trade-protection measures were introduced against sugar imports from Serbia under CEFTA free-trade conditions;

- sugar import quotas to the Moldovan market under preferential regimes are currently limited (16700) thousand tons;

- the preferential tariff quota for exporting sugar from Moldova to the EU is about 34 thousand tons per year (but in practice is not used due to high costs and/or lack of товарных resources);

- in spring 2025, beet-and-sugar sector entities received state financial support to re-sow around 5 thousand hectares of sugar-beet plantings damaged by frost;

- the new law on financial support for Moldova’s agriculture provides targeted subsidization of sugar beet.

This is not about “opening the market and closing plants,” but about creating a predictable and manageable mechanism that:

- reduces price shocks for industry and consumers;

- does not allow prices to be held up through artificial scarcity;

- incentivizes producers toward efficiency rather than perpetual requests for protection.

A healthy economy is not built on endless trade barriers and the protectionism of “a single sector with European investment” at the expense of destroying the competitiveness of Moldova’s entire food industry, but on improving productivity and efficiency. If, after two decades of unprecedented protection, the sector has ended up in a state of “free fall” in its raw-material base and unregulated end-product pricing—with strong potential for isolated domestic price growth—this is no longer “protecting the local producer.” It is postponing something very unpleasant, for which consumers—and now also Moldova’s farmers—are paying.

If sugar producers are unable to compete on equal terms with foreign companies even under current support, the rationale for continuing to subsidize their inefficiency becomes highly questionable.