Regulators place a premium on honesty and verifiability

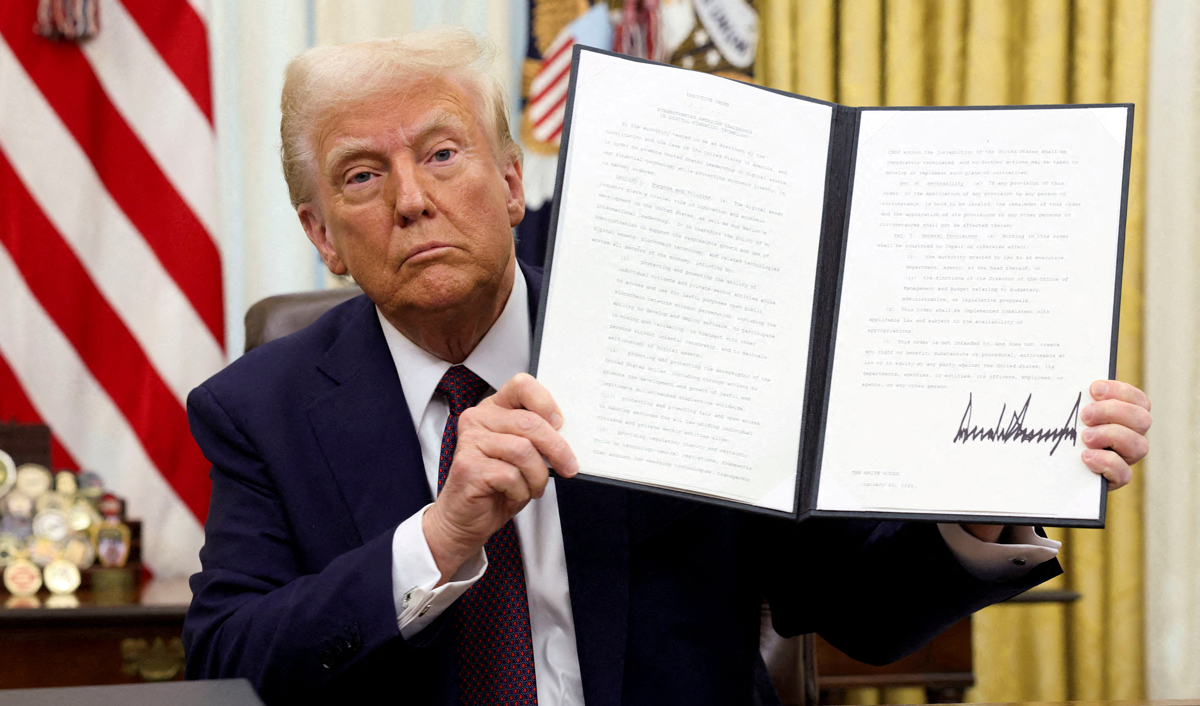

In January-February 2026, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) formalized a new approach to controlling the AI market. Instead of trying to restrict the technology itself, the regulator focused on combating misleading claims about AI capabilities and so-called AI-washing – a practice in which companies exaggerate the level of automation, accuracy or “intelligence” of their products. Reuters writes that.

According to the FTC, marketing abuses are now becoming the main source of risks for consumers and corporate clients. A spokesperson for the Commission clarified at the same time: “Our task is not to stifle innovation, but to ensure that claims about AI are accurate, verifiable and do not mislead the market.”

This approach reflects a shift in regulatory logic: AI is viewed not as an experiment, but as a mature commercial technology subject to standardized business integrity requirements.

At the same time, there is increasing pressure on the technology companies themselves. According to World Benchmarking Alliance research, only 38% of the world’s largest technology corporations publish principles for the ethical use of AI, and none of the top 200 companies disclose a full assessment of AI’s impact on human rights.

Moreover, the trend is alarming: in 2025, only 9 companies will publish their own AI principles for the first time, up from 19 a year earlier, indicating that voluntary AI responsibility initiatives are losing momentum without external pressure from regulators and investors.

Experts emphasize that the concentration of technological and infrastructure power amplifies these risks. With a few corporations controlling the majority of computing power, the lack of transparent mechanisms for assessing AI risks becomes not only an ethical but also an economic problem.

What this means for business

In this context, 2026 is shaping up to be a watershed moment for companies. The accuracy of AI claims is becoming a subject of regulatory scrutiny, boards of directors are increasingly viewing AI as a reputational and legal risk factor, and public reporting on AI is beginning to be seen by investors as a sign of mature governance.

Thus, it is clear that AI regulation is entering a practical phase: instead of general principles, verifiability, accountability and trust are coming to the fore.

For business, this means a simple but rigid formula: the larger the scale of AI use, the higher the requirements for accountability – and the more costly the lack of it.