The main catalyst for Europe’s concerns about stablecoins is the Trump administration’s Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act, which aims to promote dollar-backed stablecoins by creating a comprehensive regulatory framework for them. However, the actual provisions of the Act are very similar to those of the EU’s 2023 Markets in Cryptoassets (MiCA) Regulation, which was enacted as a precautionary measure before stable coins gained much financial significance. Thus, from a regulatory standpoint, the U.S. is not ahead of Europe. But even if it had, stable coins are ill-suited to foster the transformation their proponents expect and their detractors fear.

Stablecoins work essentially like money market funds that pay no interest: the issuer takes one unit of fiat currency from a depositor and deposits its equivalent into the depositor’s digital wallet. The main difference is that stablecoins are based on the same blockchain technology – a type of distributed ledger – that underpins cryptocurrencies.

This is where the problems arise. As the name implies, transactions on the blockchain are not processed individually, but are combined into “blocks” that are validated simultaneously, at discrete intervals. In the case of bitcoin, a single block can contain up to 4,000 transactions, and they are approved every 11 minutes or so. This makes it unsuitable for most retail transactions.

Stable coins running on newer blockchains – such as Tether (USDT), released on the TRON network – are optimized for speed and throughput. However, the transaction processing capabilities of blockchain-based technologies will always be limited, increasing the risk of bottlenecks and delays. As a result, such technologies will not be able to compete with existing retail payment systems that process transactions individually – and instantly.

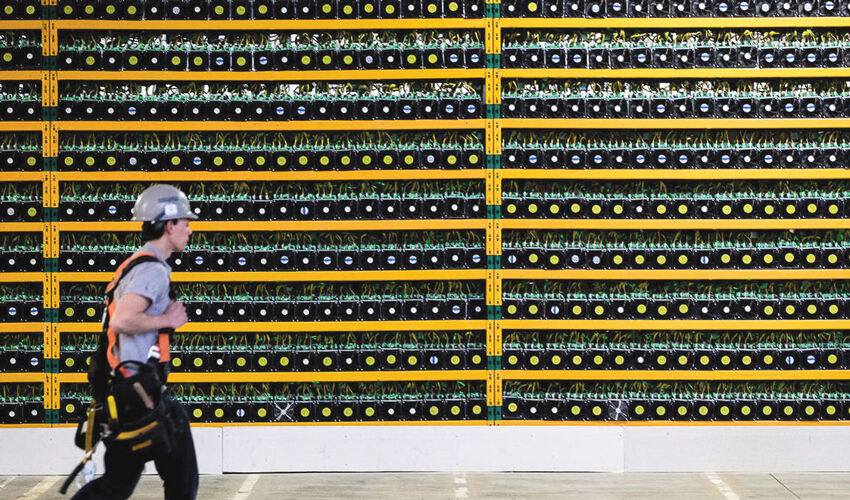

The “distributed ledger” component further complicates the situation. The basic idea of a distributed ledger is that a record of transactions (the ledger) is stored by thousands of so-called miners around the world. This is extremely inefficient (for example, TRON’s ledger contains more than two gigabytes of data), especially compared to a traditional payment system where each transaction is stored only once, in one centralized account or ledger.

Moreover, given the global distribution of these nodes, data latency and participant availability issues can slow down data validation. This further undermines the prospects of using stablecoins in everyday transactions, especially in advanced economies where fast and efficient retail payment systems already exist.

Stablecoins can be useful in cross-border retail transactions, especially remittances. However, while remittances are important to many economies, their scale is limited: about $700 billion is sent annually – less than the GDP of an average European country, and a tiny fraction of U.S. GDP. In any case, a family in a developing country receiving stable coins from a relative working in Europe or the United States would have to bear the cost of converting them into local currency (or dollar bills) to use the funds at home.

One might assume that stable coins are better suited for bulk payments: the number of transactions is much smaller, the amounts are larger, and “instant” settlement is not important. But this is also where problems arise. Transactions on the blockchain are not anonymous, but “pseudonymous“: all transactions are fully visible, but wallet owners are identified only by addresses consisting of a long string of numbers and letters. The problem is that if a vendor wants to get paid, they must share their wallet address with the customer, who can then track all future transactions with that wallet, including possibly sensitive commercial information. The customer may even share the address with the supplier’s competitors.

Criminals – such as those who conduct ransomware attacks – get around this problem by immediately redirecting payments to another wallet or even multiple new wallets. But legitimate companies can’t disguise their accounts in a way that won’t alarm potential partners and customers and possibly trigger a money laundering investigation. While there are less suspicious ways to minimize this problem, they make cash management more difficult. Stablecoins are simply not a convenient means of payment in the industry or among banks, and they are also unlikely to become a popular investment because they do not earn any interest.

Crucially, the obstacles to widespread use of stablecoins are structural: they cannot be overcome without a fundamental change in the way the instrument works. When this becomes apparent to businesses, consumers and financial investors, the current hysteria is likely to subside. Europe’s “strategic response” to the GENIUS Act should be to remain calm.

Daniel Gros,

Director of the Institute for European Policy at Bocconi University.

© Project Syndicate, 2025.

www.project-syndicate.org