What are we really counting?

The Moldovan IPC is calculated according to two main blocks:

Thefood part: It includes a fixed list of food items. This list was compiled decades ago based on basic physiological needs. It does not take into account modern dietary recommendations or changes in consumer habits. For example, it may not include exotic fruits or expensive cheese, which is the norm in developed countries.

Non-food goods and services: This category is calculated using coefficients. This is a key point. Instead of analyzing how much people actually spend on clothing, transportation, or utilities, the NBS multiplies the cost of the food basket by a fixed coefficient (usually around 1.2-1.3). This means that if the cost of food has increased by 10%, the cost of services is automatically considered to have increased by 10%, which does not always correspond to reality.

As a result, the cost of IPC for the able-bodied population differs significantly from the real costs.

Questionable data

Let’s compare the average salary, the data on which the NBS publishes, with the median. According to the NBS data, the median salary in Moldova in 2023 was just over 12000 lei per month. In turn, the median salary in the same year was only about 8000 lei. Let us note that the median salary figure is one and a half times higher, which does not reflect the real picture in the republic at all.

At first glance, even the sum of 8000 may seem sufficient. But let’s look at the structure of real expenses of an average household:

Utilities: In Moldova they can amount to 20-30% of income.

Rent: In large cities, such as Chisinau, renting a one-room apartment can cost from 3,000 to 5,000 lei, which already exceeds the subsistence minimum for 2023 (national average – 2,877.1 lei, average for large cities – 3,237.6 lei).

Transportation and communication: These expenses cannot be adequately estimated through a fixed coefficient either. Traveling by public transport within the city and traveling from the suburbs to the city to work are completely different things, and it is absolutely wrong to compare and average here.

Thus, the MPC not only underestimates real expenses, but also distorts the overall picture of well-being, making the subsistence minimum irrelevant.

IPC of Moldova vs. EU

The differences between the approaches of Moldova and EU countries to the calculation of minimum living standards are rooted in different philosophies, methodologies and, ultimately, different attitudes towards the concept of poverty.

The Moldovan IPC is based on the concept of physiological minimum. The purpose of this indicator is to determine how much money a person needs to satisfy the most basic, vital needs. It is about not dying of hunger and cold. This philosophy is inherited from the Soviet planning model, where the main objective was to ensure the basic existence of the population. This approach treats human beings solely as biological units, ignoring their social and cultural needs. As a result, the IPC represents a minimum set for survival rather than a full life.

European countries, on the contrary, are guided by the concept of social inclusion. They believe that a person living on a minimum income should be able to participate in society. The aim of reference budgets is not only to prevent physical exhaustion, but also to avoid social exclusion. This means that budgets include expenditures for access to information (internet, smartphone), cultural leisure (going to the movie theater, library), and the ability to maintain social ties (e.g., giving small gifts or celebrating holidays). This philosophy recognizes that poverty is not only a financial problem, but also a social one.

Calculation methodology

Moldova applies a static and normative methodology for calculating the IPC. The composition of the food basket is determined on the basis of outdated nutritional norms. They do not take into account modern knowledge about balanced nutrition, the need to consume certain micronutrients or the variety of foods. The list of products is fixed and has not changed for years, which makes it irrelevant in a constantly changing market.

The calculation of the non-food block is based on fixed coefficients, which are averages from past studies. For example, clothing expenditures may represent 15% of the cost of the food basket and utility costs may represent 20%. This method does not take into account that the real costs of rent or heating can change dramatically, making the whole indicator inflexible and not reflecting the real costs of the population.

Reference budgets of European countries are built on the basis of regular and large-scale sociological surveys. Analysts interview thousands of households to find out what money is actually spent on. This data gives an idea of what goods and services are really considered necessary for modern life.

The composition and cost of budgets are constantly being updated. If a new good or service becomes ubiquitous in society (e.g. access to streaming services), it can be included in the budget. This allows the indicator to remain relevant and in line with technological and social progress.

Differences in application and implications

The underestimated value of the IPC in Moldova creates the illusion that the percentage of poverty is lower than it actually is. This allows the government to avoid criticism and not to take adequate measures for social protection of the population. As a result, many people whose incomes are on the verge of survival are not officially considered poor and do not receive the necessary support.

In European countries, the picture is quite different. Since the reference budgets are realistic, they serve as a foundation for the formation of social policy. They are used to calculate minimum wages, unemployment benefits, and pensions. This ensures that even those who receive state support can live with dignity without facing social exclusion or being condemned to survival.

Budgets are calculated with an individualized approach for different types of households (single pensioner, family with one child, etc.). The composition of the basket is determined on the basis of regular sociological studies and surveys, which makes it possible to take into account not only basic needs, but also expenses for leisure, education, social integration, access to modern technologies (Internet, smartphone) and healthy food.

Key differences in methodology

|

Criterion |

Moldova (IPC) |

EU (Reference |

|

Basis |

Physiological norms, fixed coefficients |

Real household expenditures, sociological surveys |

|

Composition |

Basic food, clothing, utilities |

Comprehensive needs: from food to leisure, technology, education |

|

Purpose |

Determination of survival threshold |

Ensuring a decent standard of living, preventing social exclusion |

From stagnation to progress

The minimum consumer basket in Moldova, in its current form, is not just an outdated statistical tool, but a profound social problem. Based on this irrelevant indicator, the state cannot adequately assess the real level of poverty, develop an effective social policy and, more importantly, guarantee its citizens a decent standard of living. The outdated calculation methodology, based on fixed coefficients and physiological norms, rather than on real consumer behavior, creates a distorted picture of welfare, masking the true scale of need.

In order for the IPC to become a reliable indicator, Moldova urgently needs to undertake comprehensive reforms aimed at bringing its methodology closer to the best European practices. To achieve this goal, the following three steps are proposed:

1. Revision of the methodology: from static to dynamic. It is necessary to stop using fixed coefficients to calculate the non-food part of the basket. Instead, we should switch to regular household surveys. This will make it possible to obtain up-to-date data on the real expenditures of the population on rent, utilities, transportation, clothing, other goods and services. This approach will ensure the dynamism of the indicator, allowing it to respond in a timely manner to changes in the economy and consumer habits.

2- Updating the composition: reflecting modern life. The composition of the IPC should be expanded to reflect the realities of the 21st century. It should include expenditures that are now basic to participation in public life, including access to information, social inclusion, education and health.

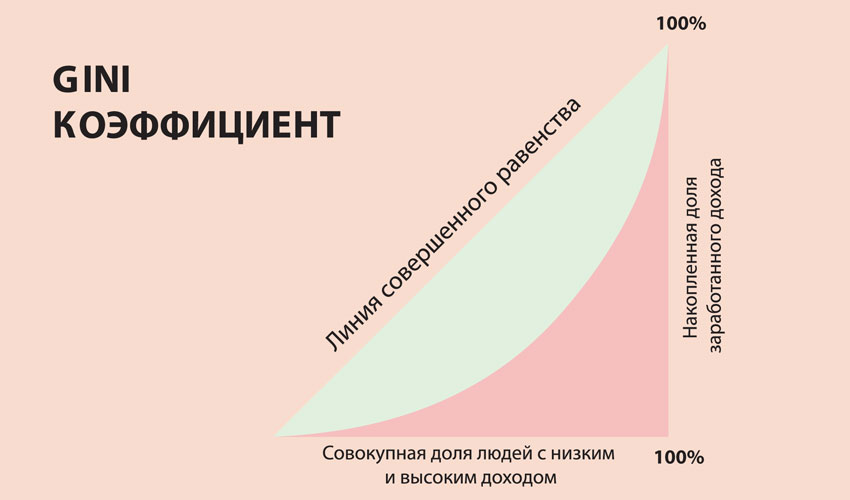

3. Integration with other indicators: the full picture. IPC should not be an isolated indicator. It should be used in conjunction with other key economic indicators such as median income and inequality (Gini coefficient). This will provide a more complete and objective picture of the population’s well-being, understanding how income is distributed in society and which groups of the population are most vulnerable.

Ultimately, reforming the IPC is not just a statistical task. It is a crucial step towards creating a just and prosperous society. Abandoning an outdated anachronism and moving to a modern, realistic welfare assessment system will allow Moldova to make better-informed decisions and effectively fight poverty, ensuring that its citizens do not just survive, but live in dignity.

Serghei MASLYANKIN,

economist