Yes, I’m biased because Wang is my friend. But I would say the same thing if I didn’t know him. And I’m not alone. Economist Tyler Cowen calls Breakneck “arguably the best book of the year.” John Thornhill of the Financial Times calls it “compelling, provocative and very personal.” Stripe CEO Patrick Collison says Wang “illuminates China like no one else.” Bloomberg’s Tracy Alloway calls him “one of the best writers on China.”

Having traveled to Canada, China and the U.S., Wang finds China and the U.S. “fascinating, crazy and bizarre.” Drive through any of these cities and you will find places that seem abnormal. He doesn’t see this as a rebuke. Unlike neat Canada, where he feels at ease, China and America show signs of being engines of global change.

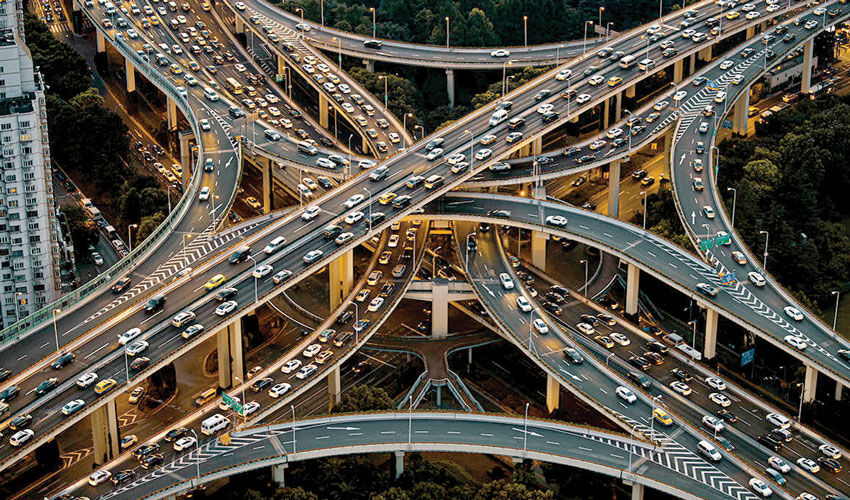

Breakneck describes China as the land of the sledgehammer and America as the land of the hammer. China’s technocratic engineering elite is solving problems with concrete, steel and scale – roads, bridges, power plants and other large-scale projects. The same impulse extends to society, as reflected in the notorious one-child policy and repression in Tibet and Xinjiang. Chinese technocracy values order, control, and visible achievement.

In contrast, the American legal elite solves problems by empowering people with property rights and security. This creates the conditions for people to live the way they want to live, and entrepreneurship and innovation become a matter of course. The reflex response to any problem is to establish yet another right or entitlement to property, drawing more people into the framework necessary for consent and approval.

Yet fundamentally, Americans and Chinese are similar – a fact that is striking when you compare the Chinese to Japanese and Koreans or Americans to Canadians and Europeans. Both peoples are restless and innovative. Both combine crass materialism with admiration for entrepreneurs. Both are tolerant of blandness. Both love competition. Both are pragmatic and often rush to work in order to “make it”. Both countries are teeming with bargain hunters and scam artists selling shortcuts to health and wealth. Both marvel at the technological ascendancy – grandiose projects that push the boundaries. The elites and masses of both countries share a credo of national greatness, represented in America by John Winthrop and Ronald Reagan’s “City on a Hill” and in China by the inscriptions “Central Country” on bronze ritual wine bowls from the Zhou Dynasty.

Both countries are also a tangle of flaws that often become their worst enemies. Old labels like “socialist,” “democratic” or “neoliberal” just don’t fit either. China is delivering rapid and visible material progress, but at the cost of diminished rights and the risk of overreaching. Its Leninist technocracy strays from the path of social engineering, moving from the practical to the absurd.

America goes astray by devoting too much time to clarifying and protecting rights, turning into a super-religious vetocracy. Safeguards curb excesses, but also breed stagnation and wasted ambition.

China would benefit from greater respect for rights and impersonal rules. But Chinese elites see little appeal in any system that might elevate Donald Trump over Xi Jinping. Equally, the US once built ambitiously, especially in the late 19th century and the post-World War II period, but now it needs to recapture that building and engineering spirit.

American sclerosis is evident even at the frontier of the global economy. Silicon Valley says it values invention but builds moats through network effects and legal maneuvers. China, by contrast, favors scale and manufacturing, following the ethos of Intel’s famed former CEO Andy Grove. If Silicon Valley or the Pearl River Delta could balance engineering scale and ambition with strong legal rights and safeguards, they would be unstoppable.

What makes Breakneck special is the way it combines theory, economic data, sociology and personal observation. Too much talk about China these days mixes distant, derivative third-hand reporting with think tank abstractions. But Wang lives the story. Familiar with the food, streets, cities, and politics in China, America, and Canada, he brings the perspective of both the local and the visiting outsider to each, allowing the reader to see, feel, and taste the places that drive the modern world. Details that appear to be color become the essence of understanding.

One of the most urgent and challenging tasks of the twenty-first century may be to create a synthesis of the best features of China and America while avoiding the worst features of each. Read Breakneck for both reportage and argument – and for reflections on the trade-offs between ambition and restraint, building and blocking, sledgehammer and hammer.

Bradford DeLong

former U.S. Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, Professor of Economics

at the University ofCalifornia, Berkeley , and author of the book

Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century (Basic Books, 2022).

© Project Syndicate, 2025

www.project-syndicate.org